AI Prototypes Are Just Prototypes

AI has made prototyping incredibly fast. A product or project manager can now go from idea to something clickable in a matter of hours, sometimes minutes. That’s a real improvement. The problem starts when this prototype is treated as a handoff to the engineering team, with the implicit expectation that they will “finish it”.

If a prototype can be produced by a handful of prompts, then the prototype itself is not the valuable asset. What matters is the intent encoded in those prompts: the flows, constraints, assumptions, priorities, and tradeoffs that guided the AI. The generated code is just a temporary manifestation of that intent. It is disposable.

Prototypes are excellent tools for validating ideas, aligning stakeholders, securing budget, or confirming that a problem is worth solving. They are not, by themselves, software. They contain none of the things that make a product viable over time: security boundaries, reliability guarantees, operational constraints, maintainability, performance characteristics, or failure modes. Without engineering poured into them, they have no technical merit.

Handing such a prototype to an engineering team and calling it a starting point creates friction almost immediately. Engineers don’t see a shortcut; they see something that must be reverse-engineered, questioned, and often rewritten. Worse, it sends an unspoken message that the hard part of the work is already done, and that engineering is just execution detail. That perception damages trust and buy-in.

It also feeds anxiety. When code generated by AI is presented as “nearly there”, it implicitly frames engineers as replaceable polishers rather than owners of the system. The result is predictable: low enthusiasm, defensive reactions, and a product that ends up being rebuilt anyway, just with worse morale.

What should be handed over is not the prototype alone, but the intent. The prompts that produced the prototype can act as a starting point for specifications. They already describe the problem, the expected behavior, and the shape of the solution. When combined with the prototype, specifications form a much stronger handoff.

This is how engineering works in most other industries. Mechanical, civil, or industrial engineers don’t receive just a written spec, and they don’t receive just a prototype. They receive both. The prototype illustrates intent. The specifications define constraints. Engineering then applies domain knowledge to turn that intent into something safe, reliable, and manufacturable.

Software should be no different.

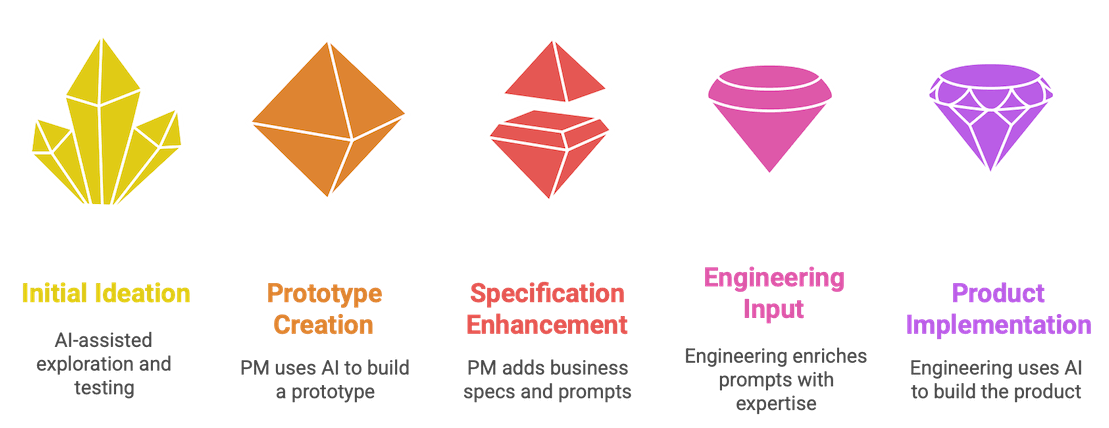

In an AI-native workflow, a PM can absolutely use AI to prototype. And that prototype should be treated as a communication tool, not a seed for production code. The real deliverable is a clear articulation of intent: the prompts, the assumptions behind them, the flows they explore, and the tradeoffs they imply. That package of prompts and prototype is what should be handed to engineering.

From there, engineering adds what only engineering can add. Architecture, security, performance, observability, deployment, long-term maintainability. Engineers may still use AI heavily to implement the system, but they do so with ownership and accountability, starting from clarified intent rather than inherited code.

This shift has real benefits for team dynamics. Engineers feel respected because their expertise is explicitly required, not bypassed. PMs retain their role as drivers of product intent rather than accidental authors of production systems. AI becomes a shared accelerator instead of a wedge between roles.

The mistake isn’t using AI to prototype. The mistake is confusing a prototype with a handoff. The future belongs to teams that hand over decisions and intent, not half-formed code.

Photo by Hyundai Motor Group on Unsplash